Information

Journal Policies

ARC Journal of Urology

Volume-1 Issue-1, 2016

Abstract

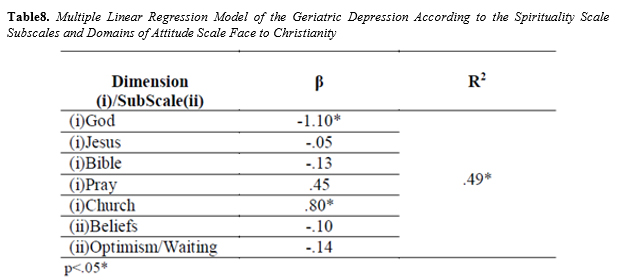

The aim of this study is to understand how religion and spirituality influence the experience of older people in institutional context. It is intended to assess the level of religiosity, spirituality and assess the prevalence of depression among the elderly. In this study participants answered the following instruments: Sociodemographic Questionnaire, Scale of Attitudes to Christianity; Spirituality Assessment Scale and Geriatric Depression Scale - GDS 15. Results showed that this sample has some depressive symptoms, and a great sense of religiosity and spirituality. A predictive model for geriatric depression showed significant results on dimensions God and Church (R2 = 0, 49; p<0.05).

2.KEYWORDS

3. INTRODUCTION

4.MATERIALS AND METHODS

5.RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

6.CONCLUSION

7.REFERENCES

AUTHOR DETAILS

Ricardo Pocinho

Coimbra Health School; Coimbra, Portugal [email protected]

Pedro Belo

Coimbra Health School; Coimbra, Portugal [email protected]

Ana Antunes

Coimbra Education School; Coimbra, Portugal [email protected]

Jose Rodrigues

Universidade Portucalense; Porto, Portugal [email protected]

KEYWORDS

Religiosity; Spirituality; Depression; Religion; Institutionalization.

Abbreviations: GDS 15 - Geriatric Depression Scale

INTRODUCTION

The scientific investment and attention given to the theme of old age and aging processes have been a constant throughout the history of mankind. Aging is associated with an increase in need for assistance [1] and is very usual people regarding the fear of dying and declining capacities with stress and anxiety [2]. There has been, by researchers in the aging, an enhancement of the effects that religious and spiritual dimension causes in individuals in order to achieve the intrinsic challenges in the aging process. Finding the patients' values, beliefs, religious and cultural needs is essential if the researcher wants to confirm the problem [3][4]. The definition of religion and spirituality can become difficult and not consensual. While religiosity refers to the level of participation or adherence to the beliefs or practices of a religious system, the concept of spirituality is broader than religion. According to [5] religiosity involves relationships with a community that shares beliefs and religious rituals. It is an organized system of beliefs, practices, rituals and symbols that facilitate the approach to the sacred and transcendent. For them, spirituality refers to assigning a meaning to life, the search for meaning and transcendence, and may or may not be connected to a system of religious beliefs. Quality of life at the end of life bonds some of the sorts of quality of life in older age. Is important retain a personal identity and a sense of self, in order to promote social contact and independence. These are important determinants of quality of life [6]. Spirituality can be defined as a process of personal change which can involve a balance of humanity and tradition. It offers people high control of their emotional and thought processes, so this could be a significant development for empowering people with dementia [7]. The dimension of the spirituality is an important aspect to consider, so will also be present in institutional contexts. It should, therefore, be understood as part of the individual aging. For [8] old age people have a need to connect with their community. Life circumstances will determine people's faith, identity and approach to spirituality. So are the life circumstances that determine people's faith, identity and approach to spirituality. The aging process requires that the individual adapts to changes and alterations that result from it. Therefore, according to [9] spirituality can be understood as a facilitating factors that adjustment. In turn, [10] argue that spirituality can be considered a dimension of the human being who seeks the attribution of meaning through the relationship with dimensions that transcend. Several practitioners, researchers have recognized the importance of religious / spiritual dimension to health [11]. To [12] religion emerges as something organizational, related to rituals and ideologies; while spirituality is associated with personal, emotional and experiential. Religion can provide a sense, a meaning to life that transcends the suffering, the loss and the perception of mortality [13]. [14] distinguish two types of religiosity: the intrinsic and extrinsic religious motivation. With regard to intrinsic religiosity religion is assumed as a central element in the life of the individual you want to live according to their beliefs, assumed to compromise. With regard to extrinsic religiosity, religion becomes a means of obtaining other purposes, occupying a surface position in one's life. Some scientific studies of spirituality domain aging and focus on understanding the relationship between spiritual coping / religious and health [15]. Coping strategies are influenced by the resources that people have, whether of external and internal nature. External features include commercial elements (eg. income, housing, status, socio-economic, etc.) and social resources (social networks, if these networks support are available). The proceeds of internal coping relate to personal, meaningful life experiences, analytical skills, beliefs and values. According to [10] religious-spiritual coping refers to the way people use their faith, beliefs, their relationship with transcendence or their connection to others as a way of adjusting and managing situations crisis. [12] argues the effect of spirituality as a mediator between stress and the emotional and physical health of the elderly. Research show that perceived control is a stronger mediator of religiousness and spirituality / subjective well-being relationship for people in later life than in the late midlife. Religiousness and spirituality have a significant impact on well-being (positive) when individuals rate lower on perceived control [16]. In this sense, it is important to understand spirituality as an important coping resource in adapting to the challenges of aging. The search for existential meaning relates particularly to religion and spirituality, for most people, particularly the elderly, there seeking answers to the crucial questions [17]. To [18], extending the life without giving a meaning to existence is not the best answer to the challenge of aging. Nowadays, the importance of good spiritual care for older people is strong, but this is not easy to achieve [19].

MATERIALS AND METHODS

The sample includes 18 elderly residents in a Regional Residence Structure for Seniors (Coimbra, Portugal). The inclusion criteria were present in the selection of participants were: (a) persons aged less than 65 years; (b) coherent speech and ability to express their views on self-determination; (c) individuals residing in the a Regional Residence Structure for Seniors.

The aim of this study is to understand how it is that religion and spirituality influence the experience of older people in institutional context and understand what the most common religious practices at this stage of life. It is intended to assess the level of religiosity, spirituality and assess the prevalence of depression among the elderly.

In this study participants answered the following instruments: Sociodemographic Questionnaire, Attitude Scale face to Christianity - Attitude Toward Christianity Scale [20]; Spirituality Assessment Scale [10] and Geriatric Depression Scale - GDS 15 [21]. The Sociodemographic Questionnaire was adapted intending to collect a set of sociodemographic data of the participants, notably including variables such as gender, age, nationality, marital status, occupation, years of formal education, religion and family support. It was also noted the reason for institutionalization as well as the length of stay in it and recorded information concerning the experience and religious practices of the target audience. The Attitude Scale face to Christianity - Attitude Toward Christianity Scale was originally applied by [20] and only focuses on the perception of people about the Christian religion. The Attitude Scale face to Christianity is a Likert type scale consists of 24 items. This scale allows us to assess the interest shown by the elderly face to religion, in particular the perception they have on the Christian religion to mention God, Jesus, the church, the Bible and pray. Spirituality Scale was built by [10] and intends to assess spirituality. The authors sought to build a simple scale, small and easy to understand, and focused questions in the spiritual dimension, attribution of meaning / meaning of life. The scale contains five items, whose answers are obtained in a Likert scale.

The Geriatric Depression Scale-GDS 15 [21] is one of the most often cited scales in the literature, both are internally validated and widely used as a diagnostic tool for depression in the elderly. It is a test for detection of depressive symptoms in the elderly, which comprise feelings and behaviours that result last week. It consists of 15 questions and answers are dichotomous (yes / no), where the outcome of 5 or more points diagnose depression, and the score equal to or greater than 11 features severe depression.

Before any intervention directed to the questionnaires was requested and granted permission to develop the research in a Regional Residence Structure for Seniors. Prior to data collection, the participants were informed of the nature and research objectives, methods, time of application and data confidentiality. The application of instruments was done through an interview individually and were respecting the ethical and formal procedures involving any research process. Data analysis was executed by SPSS 20.0 (Statistical Package for Social Sciences) performing the analysis described.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

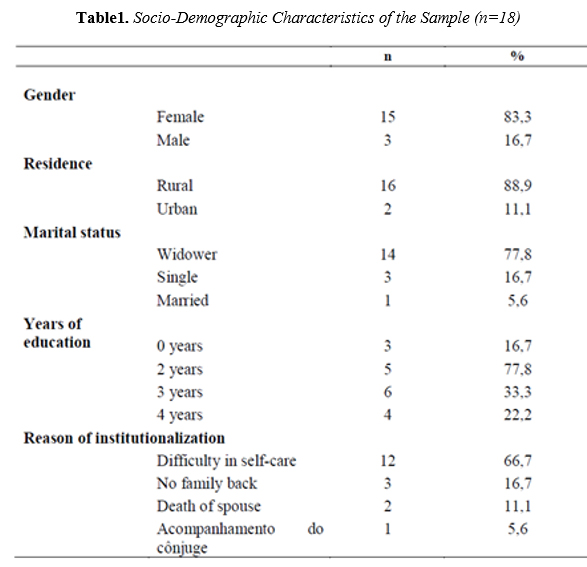

The sample consists of 18 elderly of which 83.3% are female and 16.7% are male (Table 1). Regarding the variable age, there was an average age of 82.17 years located in (SD = 6.51), ranging between 71 years and 99 years.

With regard to the area of residence (where he lived longer in his lifetime), before joining the Regional Residence Structure for Seniors in Coimbra, Portugal, it is observed that 88.9% of the subjects are from a rural area, while a minimum percentage of 11.1 % lived in urban areas. All participants are Portuguese and Catholic.

Regarding marital status, there is a high percentage of widowers (n = 14), while 16.7% are unmarried and 5.6% are married.

For the years of formal education of the participants, it is found that 16.7% did not attend formal education, 27.8% attended two years, 33.3% attended three years of formal education, and finally, 22.2% completed four years of formal education. Regarding the reason for institutionalization, it is observed that 66.7% have difficulty in self-care, 16.7% lack of family back to provide support, 11.1% due to the death of the spouse and finally, with a minimum percentage, 5 6% joined the social response to accompany the spouse.

On average the elderly are institutionalized for 47 months (SD = 42.2), ranging from a minimum of three months and a maximum of 132 months.

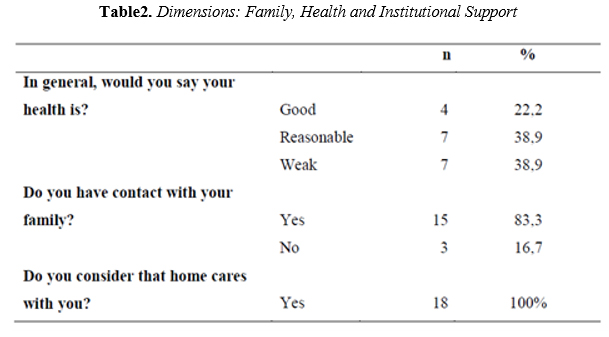

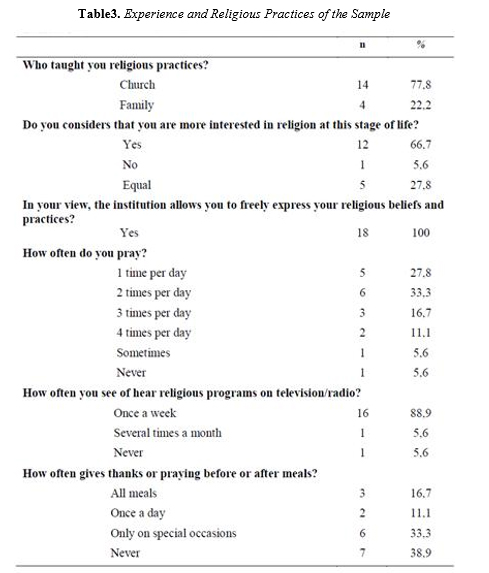

With regard to the interest in religion at this stage of life, it is observed that 66.7% consider to be interested more by religion at this stage of life, 27.8% interests in the same way by religion and 5.6% report that is no longer interested in religion at this stage of life.

As for the expression of religion in institutional context, all state that the institution allows you to freely express their religious beliefs and practices. According to the frequency of religious practice, it is found that 33.3% pray 2 times per day, 27.8% pray once a day, 16.7% pray three times a day, four times 11.1% pray per day. 5.6% say they pray from time to time and only 5.6% report ever prays. When asked about the frequency to see or hear religious programs on television or radio, 88.9% stated that it does at least once a week (Sunday), 5.6% report that makes several times a month and 5.6 % report ever see or hear religious programs on television or radio. Finally, it was found that 38.9% did not give thanks and pray before or after meals, 33.3 states that performs this act only on special occasions, 16.7% of all meals and only 11.1% do it does at every meal (Table 3).

Religiosity Analysis

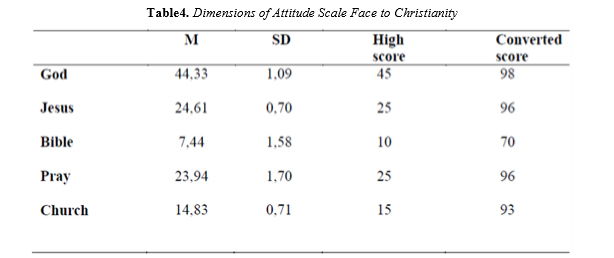

[22] refered that catholics revealed a positive relation of search for meaning with religious quest. We present below the analysis of results for each area assessed by Attitude Scale face to Christianity that focuses on topics that relate to the five components of the Christian faith, namely: "God," "Jesus," "Bible", "Praying / Prayer "and" Church "(Table 4). The total score of each domain was converted according to three simple rule once ranged the total number of items in each domain. The interpretation of the values obtained is held in observation of the converted score. Thus, we can see greater importance to "God" domain with a total score of 98 points. Still, there are very high scores, all in the 90th percentile except for the domain "Bible" which scored a maximum of 70 points.

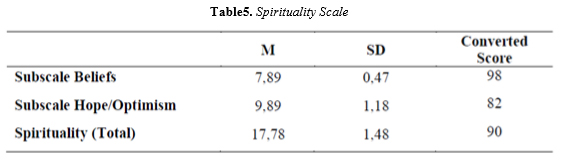

The following table shows the values obtained in the analysis of spirituality. Likewise, total scores were converted at the three simple rules, in a score from 0 to 100% for the two domains. We can thus see that there is a greater correlation with the size "Beliefs" with 98 points. The domain "Hope / Optimism" won a total score of 82 points (Table 5). Regarding the total score of the scale, it can be seen that the sample of this study presents a great sense of spiritual (M = 17.78, SD = 1.48).

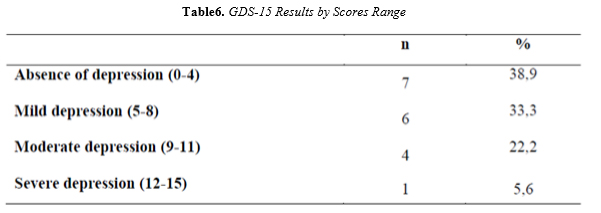

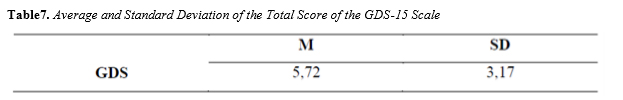

Then we present the results from the GDS-15 among institutionalized elderly. To obtain the following data was calculated the percentage of subjects relative to the sum of scores equal to or less than 4 (no depression) and percentage of subjects with a score greater than 5 (depression). Thus, it is seen that 38.9% has no depression, 33.3% have symptoms of mild depression, moderate 22.2% had depressive symptoms, and finally 5.6% have symptoms of severe depression (Table 6).

The result obtained with the model of regression in our study is in accord with the study of [23] which showed theistic factors could be predictive of psychological dimensions, as well-being or depression.

Implications

The promotion of religiosity and spirituality in the institution under study, has a great impact on the elderly experience that is institutionalized. It is a priority of the institution respect the beliefs and values of their customers and take care in giving elderly to continue to live their faith and their respective religious practices. Therefore, it is essential that institutions continue to allow religious background, allowing contribute to its customers' spiritual well-being.

With the development of this study, we notice that the most common religious practices in this sample and understand the impact of religiosity and spirituality in day to day life of the elderly residing in an institution. It was possible to verify the high sample religiosity levels, reflecting the importance of religious beliefs in the study group.

Also, some research reported that elderly respondents state higher levels of religiousness and were reported a beneficial association between aspects of religiousness and mental health outcomes [24]. Levels of happiness and psychological well-being were correlated positively with religion, however, a negative relationship are found between religion and stress [25]. A spiritual instability predicts declines in well-being by way of enlarged symptoms of depression and anxiety [26]. The difficulty in obtaining a wider sample has become a major constraint for this study. The fact that most of the institutionalized elderly in Regional Residence Structure for Seniors present levels of disability and high dependency, which prevented the application and collection of a greater number of questionnaires. Thus, the reduced sample requires paying attention to the interpretation and generalization of the results.

In this sense, it would be equally important to the future use other instruments, namely to measure religiosity, and to be more adapted to this population, which, on one hand are institutionalized, and on the other are at home, often unable to participate in practices public religious.

It is hoped that this study contribute to a current look at the old age people, based on respect for individuality, valuing your life path and respecting their personal beliefs. It urges enhance the effects that religious and spiritual dimension causes in individuals, in order to achieve meet the challenges inherent with advancing age. The religious organizations must continue providing accessibility for individuals with incapacitating conditions, once religious services improve their health [27].

CONCLUSION

The spiritual practices could stimulate some significant social and emotional benefits [28]. As regards [18], extending the life without giving a meaning to existence is not the best answer to the challenge of aging. As stated in a study of [29], the importance of religion in the life of the individual cannot influence your current mood, but over time can interfere with remission rates of depressive symptoms. In our case we highlight the importance of the Church Domain and its significant effect on geriatric depression. As the results of [30] suggested, we also agree that is necessary to promote a multidimensional groundwork of Religiosity and Spirituality for later age. The global analysis of the results shows that the elderly group has high levels of religiosity, reflecting the importance of religious beliefs in institutional environment. However religious coping aligns more with spirituality than with religiosity [30]. In this sense it is important to understand spirituality as an important coping resource in adapting to the challenges of aging.

REFERENCES

- Sorensen, S., Hirsch, J. and Lyness, J., Optimism and Planning for Future Care Needs among Older Adults. The Journal of Gerontopsychology and Geriatric Psychiatry, 27(1), 5-22 (2014). doi: 10.1024/1662-9647/a000099.

- Albans, K. and Johnson, M., God, Me and Being Very Old. SCM Press, London (2013).

- Chater, K. and Tsai, C., Palliative care in a multicultural society. Australian Journal of Advanced Nursing, 26(2), 95–100 (2008). http://www.ajan.com.au/Vol26/26-2_Chater.pdf

- Bloomer, M., Cross, W., Endacott, R., O'Connor, M. and Moss, C., Qualitative observation in a clinical setting: challenges at end of life. Nursing and Health Sciences, 14(1), 25-31 (2012). doi: 10.1111/j.1442-2018.2011.00653.x

- Moreira-Almeida, A., Neto, F. and Koening, H., Religiousness and mental health: a review. Revista Brasileira de Psiquiatria, 242-250 (2006).

- Murphy, D., Bolger, M. and Agar, R., Best practice for care in the last days of life. Working with Older People, 11(3), 25- 28 (2007). http://dx.doi.org/10.1108/13663666200700047

- Robertson, G., Spirituality and ageing – the role of mindfulness in supporting people with dementia to live well. Working with Older People, 19(3), 123 – 133 (2015).http://dx.doi.org/10.1108/WWOP-11-2014-0038

- Douek, S., Faith and spirituality in older people – a Jewish perspective. Working with Older People, 19(3), 114 – 122 (2015). http://dx.doi.org/10.1108/WWOP-03-2015-0005

- Cupertino, A. and Novaes, C. Espiritualidade e Envelhecimento Saudável. In A. Saldanha, & C. Caldas, Saúde e Idoso: a arte de cuidar. Interciência: RJ, 2004, pp. 358-368.

- Pinto, C. and Pais-Ribeiro, J., Evaluation of cancer survivors' Spirituality: implications on quality of life. Portuguese Journal of Public Health, 28(1), 49-56 (2009).

- Moreira-Almeida, A., Espiritualidade e saúde: passado e futuro de uma relação controversa e desafiadora. Revista Psiquiatria Clínica, 34(1), 3-4 (2007).

- Pargament, K., The psychology of religion and spirituality? Yes and No. International Journal of the psychology of religion, 9(1), 3-16 (1999). doi: 10.1207/s15327582ijpr0901_2

- Goldstein, L. and Sommerhalder, C., Religiosidade, espirtualidade e significado existencial na vida adulta e velhice. In E. Freitas, L. Py, A. Neri, F. Cançado, M. Gorzoni, & S. Rocha, Tratado de Geriatria e Gerontologia. Guanabara Koogan: RJ, 2002, p. 951.

- Allport, G. and Ross, J., Personal Religious Orientation and Prejudice. Journal of personality and social psychology, 5(4), 432-443 (1967). http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/h0021212

- Dalby, P., Is there a process of spiritual change or development associated with ageing? A critical review of research. Aging & Mental Health, 10(1), 4-12 (2006). http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/13607860500307969

- Jackson, B. and Bergeman, C., How Does Religiosity Enhance Well-Being? The Role of Perceived Control. Journal of Psychology of Religion and Spirituality, 3(2), 149-161 (2011). doi: 10.1037/a0021597

- Oliveira, J., Psicologia do idoso - Temas complementares. Livpsic/Legis editor: Porto 2008.

- Neri, A.L., Maturidade e velhice. Papirus: Campinas, 2001.

- Perkins, C., Promoting spiritual care for older people in New Zealand: the Selwyn Centre for Ageing and Spirituality. Working with Older People, 19(3), 107 – 113 (2015). http://dx.doi.org/10.1108/WWOP-01-2015-0003

- Francis, L., Measurement reapplied: Research into the child's attitude towards religion. British Journal of Religious Education, 1, 45 – 51 (1978).

- Sheikh, J. and Yesavage, J., Geriatric Depression Scale (GDS): Recent evidence and development of a shorter version. Clinical Gerontology: A Guide to Assessment and Intervention, 165-173 (1986).

- Steger, M., Pickering, N., Adams, E., Burnett, J., Shin, J., Dik, B. and Stauner, N., The Quest for Meaning: Religious Affiliation Differences in the Correlates of Religious Quest and Search for Meaning in Life. Journal of Psychology of Religion and Spirituality, 2(4), 206-226 (2010). http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/a0019122

- 23. Currier, J., Kim, S., Sandy, C. and Neimeyer, R., The factor structure of the Daily Spiritual Experiences Scale: Exploring the role of theistic and nontheistic approaches at the end of life. Psychology of Religion and Spirituality, 4(2), 108-122 (2012). http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/a0027710

- Idler, E., Musick, M., Ellison, C., George, L., Krause, N., Ory, M., Pargament, K., Powell, L., Underwood, L. and Williams, D., Measuring Multiple Dimensions of Religion and Spirituality for Health Research: Conceptual Background and Findings from the 1998 General Social Survey. Research on Aging, 25(4), 327–65 (2003). doi: 10.1177/0164027503252749

- Rowold, J., Effects of spiritual well-being on subsequent happiness, psychological well-being and stress. Journal of Religion and Health, 50(4), 950-963 (2011). doi: 10.1007/s10943-0099316-0. .

- Sandage, S. and Jankowski, P., Forgiveness, Spiritual Instability, Mental Health Symptoms, and Well-Being: Mediator Effects of Differentiation of Self. Journal of Psychology of Religion and Spirituality, 2(3), 168-180 (2010). doi:10.1037/a0019124 32

- Benjamins, M. and Finlayson, M., Using Religious Services to Improve Health: Findings From a Sample of Middle-Aged and Older Adults With Multiple Sclerosis. Journal of Aging and Health, 19(3), 537-553 (2007). doi: 10.1177/0898264307300972

- Lindberg, D.A., Integrative review of research related to meditation, spirituality and the elderly. Geriatric Nursing, 26(6), 372-377 (2005). doi:10.1016/j.gerinurse.2005.09.013

- Koening, H. G., George, L. K. and Peterson, B. L., Religiosity and Remission of Depression in Medically Older Patients. American Journal Psychiatry, 155(4), 536-542 (1998). http://dx.doi.org/10.1176/ajp.155.4.536

- Jackson, B. and Bergeman, C. S., How does religiosity enhance well-being? The role of perceived control. Psychology of religion and spirituality, 3, 149–161 (2011).